Slow fashion designers say Indian consumers tend to gravitate towards cheaper prices and brighter colour palettes.

But they’re geared for the road less travelled.

◊ By Mili Doshi. Images by Mili Doshi & Karen Fereira

Visit ORGANIC SHOP by Pure & Eco India

The recent years have seen our country waking up to a clarion call of circularity and sustainability.

With trailblazers across industries helping the country clean up its act, it seems like we are finally—albeit slowly—moving towards the day when conscious clothing will no longer be an alternative utilised only by the well-heeled.

It is particularly interesting to chart this phenomenon in a city that is as multidimensional as Mumbai. Amid scores of heavyweights swarming the scene, a world full of hopeful, homegrown and under-the-radar ethical labels heaves beneath.

While one may employ a frill-free aesthetic to integrate slow living into clothes, the other introduces innovation and an eclectic colour palette to prove that sustainable clothing goes beyond humdrum greys and whites.

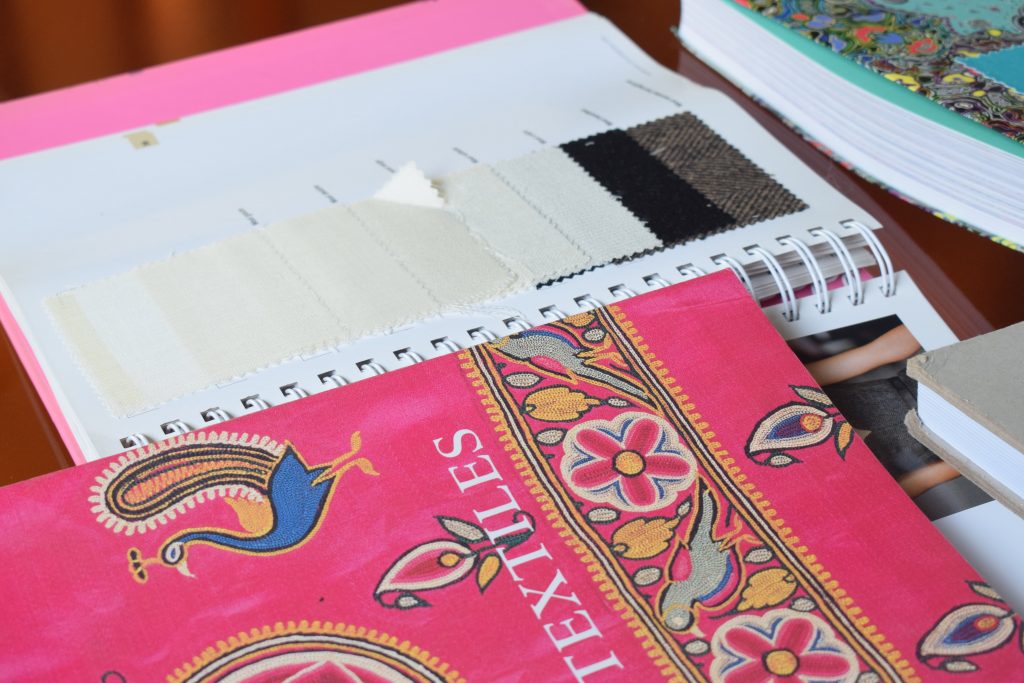

Toiling in their little ateliers, these designers are doing all that they can—from using organic fabric and fairly paying weavers to upcycling scraps—to be mindful and ethical businesses.

ITO INDIA

A jaunt through the rickety lanes of Malvani, a suburban pocket in Mumbai, reveals the factory space in which the studio of Ito India is located. Ito is the labour of love of design graduate Shivani Gandhi, who creates minimalist dresses and waiflike midis.

Ito is homegrown in the truest sense of the word. Gandhi employs housewives living in and around Malvani for her embroidery. The neighbourhood is brimming with karigars skilled in embroidery, fabric printing, etc.

Shivani Gandhi, designer, ITO, in one of her creations

Although Gandhi’s designs lean towards minimalism, the labour that goes into them is not minimal, shares the designer. “Just because it is slow fashion, people think that these are simple designs, and by extension, easy to execute,” she says.

Embellishments such as dainty hand-embroidered Ito imagery and hand-cut scalloped trimmings stitched on to the hem and neckline—all enmeshed in a colour palette of white, sage, and pale yellow—render the label a dream for those with a taste for simplicity and minimalism.

Shivani’s first collection, ‘New Beginnings’ was crafted entirely from mulmul (muslin) and handloomed cotton. While the collection is inspired by the British countryside, ‘Late Comers’, a sleepy, laidback extension of the former, depicts afternoon siestas and lived-in mornings.

The Damsel Mini dress crafted from mulmul (muslin)

Wispy Kurta made from mulmul

The label works closely with fairtrade collectives; and its textile repertoire predominantly comprises jamdani, linen, cotton, and chanderi, handspun and handwoven by artisans in Madhya Pradesh and West Bengal.

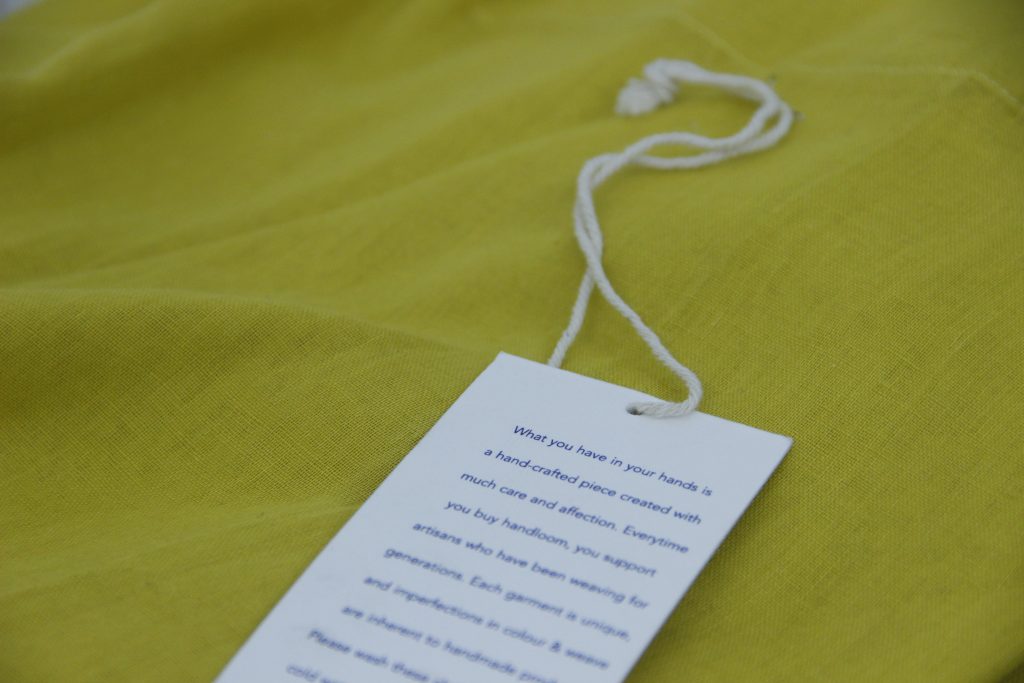

The label prides itself on being ‘entirely ethical’, wherein every stakeholder along the supply chain is paid fairly and operates in a safe environment.

The challenge that Gandhi faces with consumers is that many are drawn to vibrant colours and accentuated patterns. This proves to be a point of friction for Gandhi whose designs are considered ‘too plain’ by some.

“Neutral clothes can sustain themselves. With muted shades, there is much more scope for internal layering. I want people to keep and use, and not use and throw,” she says.

ANUSHÉ PIRANI

Inside Anushé’s studio, the first thing I drifted towards was a life-size installation made of waste fabric scraps deftly patched together.

This, accompanied by the understated furniture, set the tone of the label in my mind’s eye. Pirani got her foot in the designing door in 2017, with the launch of her first collection, titled ‘The Beginning’.

The ‘Period Play’ collection by Anushé Pirani

Anushé Pirani, in one of her creations

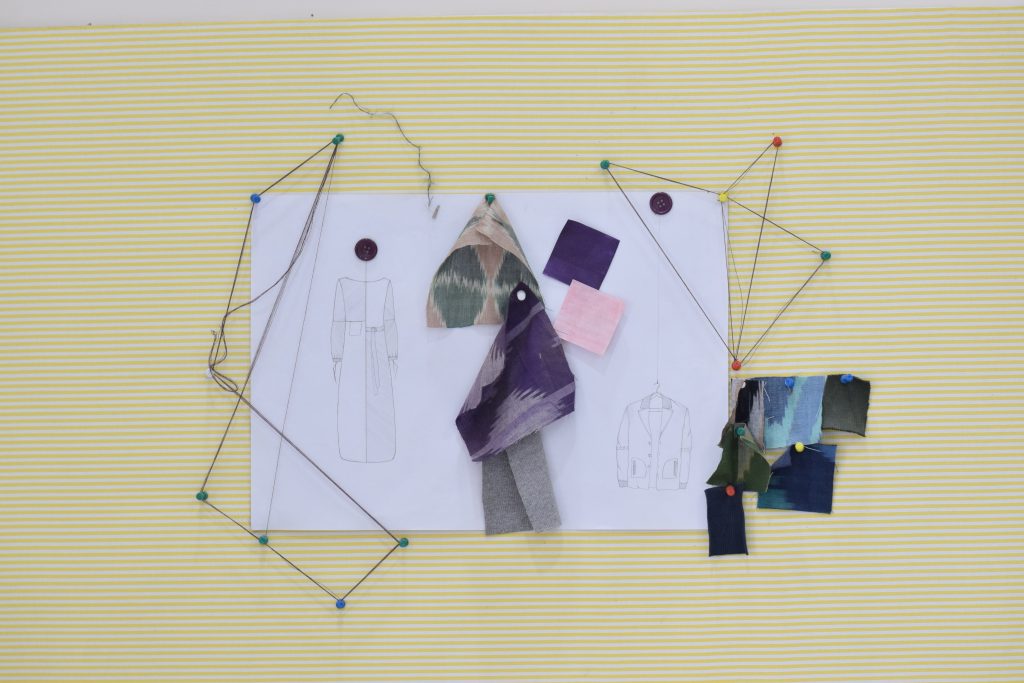

“When you’re making a garment, it needs to have some story, a context that connects somewhere,” she says. Case in point: in one of her collections, ‘Period Play’, she has drawn a narrative around punctuation marks, and the way in which they shape everyday communication.

With the base fabric being jute khadi, each piece from the collection is adorned with one or more punctuation marks made with hand-loomed cotton.

Woven into the fabric through the reverse appliqué method, these punctuated details (a hyphen stitched on to a sleeve or a full stop represented by a circular pocket) particularly stand out because of their distinctive shapes and pastel palette.

Pirani’s Resort line featuring Ikat separates

Anushé lends a quirky spin to otherwise banal items of clothing— deconstructed designs enlivened by the occasional pop of colour. She lays emphasis on comfort and versatility as reflected in her creations— the jackets that double as dresses, and shirts that boast detachable sleeves.

The eponymous label draws generously on nature and architecture. Anushé’s clothes also carry traces of androgyny, which plays well into the brand’s non-conformist stance. Although, she reveals, “We don’t dabble in androgyny consciously. The design almost always takes its own course.”

One of her collections, ‘Desert Bloom’, involves ikat handwoven by artisans from Telangana. This, she says, is the underlying essence of her brand—translating indigenous weaves into contemporary renditions.

Anushé’s brand endeavours to be as much a space for men as it is for women. “Men in Mumbai face a dearth of sustainable clothing options. So we have made it a point to include menswear pieces in our collection,” says Pirani.

IYLA

I climbed three flights of stairs to get to Shreya Anand’s studio and was greeted by a sun-dappled terrace rife with potted plants of varying shapes and sizes.

Before I could completely imbibe the emerald-hued oasis, Shreya summoned me to the adjoining studio. Inside, more plants lined the window, while Ella Fitzgerald played in the background. “I’ve built myself a little sanctuary here,” Anand gushes.

A SARA Ikat dress by IYLA

A KIRA block dress made with handloomed cotton

Shreya Anand, designer, IYLA, in one of her dresses

Our conversation instantly developed around time and how it is a prerequisite for any sustainable label to flourish. “If you look at the trajectory of some of the prominent handloom textile brands—Anavila, Raw Mango, or Maku Textiles—it has taken them a while. Péro has taken years to get to an international level. So it’s a long haul,” she says.

Anand is geared for the slog. “At Iyla, I don’t intend to produce four collections a year until I clean up my brand’s ecosystem and inner processes.”

With handloom in particular, the process can’t be rushed—just the creation of a fabric takes about two and a half months, not to mention dependence on the weaver.

“Getting the weavers to be more streamlined and professional is taxing. There was a time in 2018 when I kept rejecting metres upon metres of fabric because it was nothing close to what I had envisaged. This happens because it is crafted by human hands. For a start-up to absorb such setbacks is huge,” she explains.

Anand’s love for scuba diving is reflected in one of her collections, ‘What Lies Beneath’. She picks up her navy blue Bria ikat dress to demonstrate what went into the making of it. “This is an adaptation of a 35-year-old vintage Japanese ikat, which is originally done on 10 inches of fabric. We have adapted the design and re-interpreted it on a 45-inch fabric,” she says.

Shreya’s work carries traces of music, cinema, and art. Her creations draw heavily on nature, surrealism, and geometry, while taking cues from some of her most beloved artistes, such as Hayao Miyazaki and Imogen Heap.

In a time dominated by mass-market goods, it can get daunting to wrap one’s head around organic fashion and why it’s so important, and moreover, to sell it to the audience. “Today, you see retailers offering clothes worth (INR) 799 and 999, and it sells. So when the audience, too, is looking for instant gratification, how does a label like mine survive?” she ponders.

As a stylist having had a strong footing in Bollywood, Shreya used to be constantly in and out of H&M and Zara outlets. But with the birth of Iyla came a conscious decision to draw the line.

“As a creator, you have to decide to stop consuming more. Your niche clientele understands this, but when they, too, are downsizing their wardrobes, it helps my cause. I limit my production to only two collections a year,” she explains.

With handloom placed at the heart of Iyla, Anand does not conform to sack-like silhouettes and the hackneyed definitions of sustainable fashion.

The kimono-like Turin dress, the cascading Zola jacket, and the colour-blocked Halena dress, which is inspired by the corals of the ocean, submit proof of her creations’ exuberance.

For Shreya, familiarising her brainchild with the masses is important but there are more pressing matters at hand in the current moment. “I am keen on documenting the process of my creation. I have figured out who my organic cotton suppliers would be, and I am also looking at venturing into block-printing,” she shares.

THE PLAVATE

The Plavate’s Meenu Tiwari says, “We may be small now, but our craft is of high calibre.”

Plavate, which means ‘flow’ in Sanskrit, attests to Tiwari’s silhouettes which are a modern-day response to traditional weaving techniques.

For her collection ‘Join the Dots’, she predominantly worked with weavers from Bhopal and West Bengal. A canvas of subdued polka, the collection features handwoven khadi-cotton interspersed with jamdani motifs.

A ‘Drop of Dewdrop’ Dress with finely weaved jamdani circles – from the ‘Join the Dots’ collection by The Plavate

The designer believes there is much room for innovation when it comes to age-old textiles. “Khadi is quite interesting to work with. The reason some may find it otherwise is because we are used to seeing it in a monotone sort of way,” she says. She aspires to disrupt this cycle of monotony and introduce a new perspective to the traditional fabric.

Established in January 2018, The Plavate, as a brand, is conscious of its consumption, striving to function on a zero-waste model.

With each collection, Tiwari’s team recycles the pieces into samples that serve stencils for upcoming pieces. “We use selvage extensively in our designs,” she shares, while rummaging through bales of fabric to look for a katran (scrap of cloth).

With power looms swiftly taking over urban clusters, the handloom industry across India has been plodding of late. “One way to mitigate this is by paying the weavers well. I want to strive towards the financial well-being of as many weaver families as I can,” Meenu says.

A pressing concern for her, however, is patrons’ response to pricing. “Experimenting with sustainable materials is an expensive affair, which encompasses weavers’ wages, investing in the best of fabrics, transportation costs, and so much more.

“I sincerely wish that people truly started acknowledging the effort of everyone across the supply chain, which goes into the final product. That is the only way old traditions, indigenous artisans and traditional textiles can be retained and honed,” she concludes.

Leave a Reply