Having orchestrated organic certification, tech support and market linkages for 250,000 small farmers across India, GDC-backed Morarka Foundation, is leading the organic farming movement in the country since 1995.

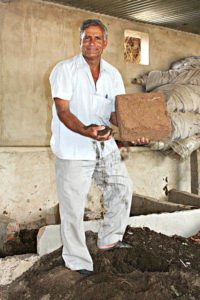

By Lily Tekseng (Pictured above: Award winning farmers, Santosh and Jabharmal Pachar of Sikar; all photos © Benefit Publishing Pvt Ltd)

Note: To access the contact details of all Indian organic suppliers and organic shops in India, buy Organic Directory

Few are aware that Mukesh Gupta, executive director of one of India’s pioneering and largest organic food development foundation and a recent company, namely Morarka Organic Foods Ltd, began his career working as an up-and-coming executive for a prominent pesticide firm. Back in the early 80s, Gupta was a fresh faced MBA and agriculture engineer working in the pesticides division of Excel Industries, marketing exactly that—chemical pesticides.

Morarka’s Down to Earth range

Ironically, it is this stint with the chemical maker that caused the important change of trajectory in his otherwise long and illustrious career—it sowed the seeds of disillusionment with the pesticide industry and compelled him to travel to the other end of the spectrum—organic agriculture.

While Morarka’s attempt to promote organic farming may have started from tiny Nawalgarh, it must be acknowledged that the attempt has now evolved into a movement of pan India proportions, with 2.5 lac partner farmers on the Foundation’s watch

“During my time working with pesticides, I observed on many occasions certain unscrupulous agriculture scientists approving unnecessary new pesticides as ‘Requisite’ for a picayune Rs 5,000,” divulges Gupta. “I realised very quickly that many of the pesticides being listed were gratuitous and were being approved for mere personal benefit with no regard to land, farmer, or consumer!” he exclaims.

There was also the instance when a certain pesticide he was marketing started posting record sales in West Bengal and when out of curiosity, Gupta reached the interiors, to his horror discovered that the pesticide intended to ward off pests in farming, was being tossed freely in the waters, killing fish by the thousands; unethical fishermen were the real source of the groundbreaking sales figures. “I left fish for a long time after that,” remembers Gupta.

Mukesh Gupta, executive director, Morarka Foundation &Morarka Organic Foods Ltd

He also left the pesticide industry—for good. For many decades now, Gupta has been an eminent figure in the global organics industry. Among his various roles over the years, he has been Advisor to the Ministry of Agriculture, Government of India, for preparing roadmap of organic farming in India in 2001, and President of the International Competence Centre for Organic Agriculture (ICCOA). He has also authored several books on organic farming techniques, such as Organic Agriculture Development in India, and Organic Agriculture-Micro-planning and Certification. He was also involved from 1995 onwards in the certification of farmers in USA, Latin America, Malaysia, Europe, etc, and then eventually in India through his association with the International Foundation of Organic Agriculture (IFOAM).

Gupta informs how pesticides came to be used for farming purposes. “Pesticides were first developed during World War II as chemical warfare agents. After the war, it was discovered wherever these chemicals were used, crops had thrived and pests were absent. Thereafter chemicals like organophosphate compounds were repurposed as pesticides,” says he.

But over a period of time, pests and the land became immune to the chemicals, requiring more and more to acquire the same results over the years. A staggering number of pests and weeds have developed pesticide resistance since pesticides first came into existence in 1945. These chemicals also started to cause health problems for humans. Thus, the need for sustainable organic farming without pesticides began to take root.

Journey towards Organic

Morarka Foundation’s journey started in Nawalgarh, a small rustic town in the Shekhawati region (a semi arid historical region located in northeast Rajasthan), where the Foundation’s founder, Kamal Morarka, has his roots. In 1993, Morarka, who is also promoter of multinational construction company, Gannon Dunkerley & Company (GDC), established the Foundation in his late father’s memory in an attempt to uplift Nawalgarh, the land of his ancestors.

The topography of Rajasthan is tough, the land arid, the climate extreme and rain sparse. Years of pesticide use had made pests immune and the land unyielding, leading to widespread poverty among the farmers. Therefore, Morarka decided to initiate organic farming in the area as a way of reviving the land, improving economical conditions for the farmers and creating sustainable livelihoods for them for the unforeseen future. To prepare the land and its people for an organic way of farming was a challenge that was sisyphean at the start. The beginnings were humble. It started with the training of 10,000 farmers in Sikar, Jhunjhunu and Churu districts of Rajasthan.

But what started as a dutiful tribute to one’s father has now spread into what is today a revolution of 250,000 farmers converted to organic farming across the country. Today, Morarka has partnered with 75,000 farmers in Rajasthan alone, with approximately 1,000 new farmers converting to organic farming with Morarka’s assistance annually. Furthermore, the Foundation has collaborated with private and government institutions in Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand, UAE, Costa Rica, US, UAE, Saudi Arabia and Europe in sharing sustainable organic agriculture practices.

After tying up with almost all the farmers in the Nawalgarh region and receiving a successful response, the Foundation decided to launch an entire range of products as a way of providing market linkage to the farmers who lack business savvy and resources. It tied up with Sikkimese farmers for their organic ginger, Gujaratis for their Kesar mango, and Maharashtrian farmers for soya and urad dal, to name a few.

Thus, the Foundation became the first to introduce organics across Asia in 1995. Outside of Europe, Morarka Organics is also supposedly the first company to have launched a dedicated range of organic foods in many Asian countries—its Down to Earth brand. Today, the Foundation enjoys 1,500 stakeholders that are supporting farmers along with Morarka; 250,000 certified farmers; and 2,500 retail points for Down to Earth pan India, as well as, abroad.

However, the journey to success has been uphill, punctuated by many a hindrance and disappointment. “The resistance we felt from the science community and policy makers at every level and corner was pervasive,” recounts Gupta. The notion that there could be a sustainable alternative to pesticides was unfathomable, and the benevolence of the chemical input industry far too insidiously entangled with the scientific community. However, with his agriculture engineering background, as well as, his first hand knowledge of pesticides, Gupta was able to argue successfully for the merits of organic farming.

Multipronged Endeavors

The role of Morarka Foundation in helping farmers convert to organic farming has been tremendous and includes many facets. The Foundation has democratised organic farming by making it accessible to small farmers, whereas earlier, it was perceived as a novelty only affordable by the wealthy. Morarka devised a new, more feasible practice: Certified small farmers with small outputs collectively making up large marketable volumes. This simple yet powerful method made it possible for small farmers to thrive as organic farmers and generate additional employment for family members as well.

Morarka gives the farmers fillip by sponsoring organic group certification authorised by government certification agencies like Onecert and others. It also provides them with the technology support required to get the organic farm started. Frequent demonstrations and training workshops are conducted imparting the various nuances of organic farming. Regular congregations are held, literature in the local dialect disseminated, monetary succor lent, paper work filled out for the less literate—no stone has been left unturned, it seems, in the endeavor to ubiquities organic farming in the country.

Contraptions like the Chakravyooh are often used by organic farmers to curb pests naturally

Technical information on how to ensure healthy crops without using chemicals, as well as, reduction of cultivation costs form an important part of the training. For instance, a herbal spray made of neem, cow urine, bougainvillea and papaya leaves, onion, ginger, and green chilli acts as a strong (and economical) natural pesticide. Vermiwash, a liquid made by filtering water and earthworm in silt and cow dung, utilises hormones found in earthworms to ensure the good health of the plant between flowerings to fruition. Simply treating seeds in cow urine wash goes a long way in ensuring healthy crops. This information aims to emphasise biological fertility management rather than chemical. Biology promotes a probiotic effect on soil, both above and below ground—making up for the substitution of chemicals.

Vermicompost proves to be a good natural fertilizer

The Morarka Research Centre in Nawalgarh assists the Foundation by carrying out further research and development in the field. It also provides (gratis) partner farmers with coco peat, earthworms for vermicompost and Natural Sustainable Decomposting Liquid (NSDL), a Morarka product that is a microbe-rich natural fertiliser used with cow dung.

The creation of market linkages, which Morarka undertakes for the farmers, is crucial to the development of organic farming in the region. “Wherever market linkages have been initiated, farmers have adopted organic practices increasingly in those areas (sic),” says Kuldeep Raka, Commissioner, Ministry of Agriculture, Rajasthan.

The concept of Value Chain Management in organic agriculture is also being actively promoted by the Foundation. It is a system for small farmers to come together to aggregate their produce in order to make large volumes for value addition, branding and premium marketing. This helps farmers to optimise their consumer spend. For instance, if they were getting Rs 11 for 1 kilo of wheat grain individually, they can expect Rs 17 per kilo collectively since they have adopted organic and their collective volume has now increased.

In an endeavour to promote organic farming even further both with the farming community, as well as, government authorities, Morarka hosts two large events every year—Krishi Sammelan (Farmers’ Meet) during the Chairman’s visit to the various villages in the month of September and, the Shekhawati Organic Food Festival in February every year since the last 20 years—both in Nawalgarh. “We organise the Krishi Sammelan as a platform to educate farmers on the virtues of organic farming,” says Verdhman Bapna, General Manager, co-ordination, Morarka Foundation.

Farmer Success

Surender Singh Ladwal in his green shade net

In organic farming, the ultimate objective of farming as promoting farmer welfare is fulfilled. The farmer grows healthy food on healthy soil that he sells, as well as, consumes. He incorporates the use of farm animals and also employs his own family members—everyone is taken care of, and the farmer emerges profitable, the land supple and fertile.

What is wonderful about the farmer-benefactor pairing is that both parties—Morarka and the farmer involved—are unbound by obligation. The farmer, despite having received organic certification of his farm through Morarka, is free to sell his produce to whoever he likes, come harvest. This is key to the democratisation process and farmers are benefiting.

In 2013, Santosh Pachar and her husband, Jabharmal of Sikar District, were awarded by the President of India for their “improved variety of carrots”. Prizes are a routine affair for the duo, whose organic certified carrots are as long as two and a half feet. Panchayat (village council), Zila (district council), and state level trophies and medals are proudly showcased in their living room, their album bursting at the seams with newspaper cuttings singing praises of their produce.

The Pachars’ carrot saplings are treated with desi (pure)ghee and honey, and are thusly sweeter and more robust than their peers. The successful couple also cultivates organic chillies, tomatoes, cluster beans, and onion, as well as, trades online under the entity name, Santosh Agro Farm. The Pachars are one of the many farmers in Shekhawati, who have received organic certification through the Foundation.

Om Prakash sells organic vegetable saplings to the tune of Rs 45 lac per annum

Om Prakash, a farmer in association with Morarka since 13 years has become a poster boy for organic farming in the community due to his high earnings through organic cultivation. Today, he sells organic vegetable saplings in north India to the tune of Rs 45 lac per annum with an RoI of Rs 20 lac. For “petty change” he also sells vegetables worth Rs 1.2 lac per annum. With the business soaring, Om Prakash has laid out fresh plans for a new business venture, his own brand of organic vegetables, by the name of Om Organics. He has taken 35 acres on lease and plans to expand his vegetable cultivation further.

Om Prakash’s famous organic green chillies

Another farmer, Surender Singh Ladwal from the village of Laxman Ka Baas returned a few years ago from Dubai to his 4-acre farm. Since the last five years, he has been working as a partner farmer with the Foundation, and the results are encouraging. His farm has a green shade net of roughly 0.5 hectares where he grows tomato, chilli, cucumber and Thai apples. Besides the green shade net, Ladwal’s farm is also decked out with sprinkler irrigation and a fogger system to control temperatures. The installation of these devices requires technical know how and navigation of various government departments for release of funds meant for assistance to farmers—all facilitated by the Foundation.

Dhruva Rajnish Lamba of Dehar Chailasi village in Jhunjhunu district is a first generation convert to organic farming. His father, also a farmer, used to use chemical fertilisers extensively. About five years ago, Lamba decided to go completely organic and invest all his energies into creating an organic horticulture farm—the only in Nawalgarh. His 3.9-hectare farm houses 1,300 sweet lime trees, 600 Beel trees, 100 kinnow (Mandarin hybrid) trees, 600 pomegranate trees, and 250 lemon trees. It’s a long term investment but he expects returns of Rs 20 to 25 lac in the future. From the initial harvest of kinnow, sweet lime, and beel, he has earned about Rs 2.5 lac so far this year.

The Lamba brothers at their organic horticulture farm in Jhunjhunu

The farmers are grateful to Morarka for the spoon feeding. Individual certification costs as much as Rs 2.5 lac, which has to be renewed every year. Group certifications are less expensive, costing between Rs 2,000 to 5,000 for each farmer in a group of every 500 farmers, but the formalities are long and convoluted. “I’m educated so I could have filled out the paper work for the organic certificate but could not have afforded the exorbitant cost for the same,” says Ladwal.

Way Forward

Recent media reports of food contamination and adulteration have roused the fears of a vast majority of people in the country. An increasing number of consumers now want to know where the food they eat comes from and what its quality ought to be. The last five years have seen a major shift in attitude at the consumer end as demand for certified organic foods has increased. “This development will prove to be a game changer for the organic food industry,” points out Gupta.

But government succour is the need of the hour to put plans into action. The Modi government has allocated Rs 300 crore to organic agriculture this year. With ambitious plans of making many states in the Northeast 100 percent organic this is being further supported. “However, a lot will depend on how the allocation is spent eventually,” says Gupta.

Certain government regulations hold back the organic industry, opines Gupta. For instance, the National Programme for Organic Production (NPOP) certification for export is not valid in the US, and therefore redundant, but is still demanded by domestic authorities. Moreover, the government can also aid the industry by creating awareness through campaigns and associations.

Government support or not, Morarka is ploughing ahead. Among its future plans are promoting urban farming in cities by providing technology support to entrepreneurs in the field. Plans are also afoot to take the Organic Lunch, an event that provides an interface between organic consumers and producers, to 10 more cities in the country, and also bring organic food to commercial food catering like canteens, conferences, etc.

Having succeeded on the domestic front, Morarka’s export business, too, is witnessing a surge in demand. The export mainly comprises pulses and grains for which there is a robust requirement in the US and Europe.

While Morarka’s attempt to promote organic farming may have started from tiny Nawalgarh, it must be acknowledged that the attempt has now evolved into a movement of pan India proportions, with 2.5 lac partner farmers on the Foundation’s watch. The atmosphere in the country is more conducive today for organic foods and farming; it was a lonely journey for the Foundation to hack away unheard at rigid rules and unsympathetic policies. But with the changed consumer climate, the naysayers seem to have lowered their pitch. “Yes, the ‘Nos’ are less vehement now but I do still get the odd acidic letter,” smiles Gupta.

Other CSR Initiatives of Morarka Foundation

Self Help Groups

The beautiful ladies of the Nawalgarh SHG show off their bank passbooks The Foundation assists in the functioning of hundreds of Women’s Self Help Groups (SHGs). Vinod Devi, Programme Officer, leads 285 SHGs, and boasts of 2,800 members spread over 38 villages in the area. What the SHG essentially does is help the women save money for emergencies. All SHG members contribute a quantum per month, which is recorded and put away in the collective bank account of the group. When a woman needs a large sum, she is granted a loan from the bank account of the SHG and can repay it at a lower rate of interest than the bank. These women benefit in that they are able to make bank accounts which they could not have done by themselves, being uneducated and suppressed in a deeply patriarchal setting. Two, they are able to save in a safe place, ie, the SHG account—at home, drunkard husbands, abusive in laws snatch money away. Thirdly, when an emergency strikes, they can forego the tedious paperwork required for bank loans; the SHG offers instant respite to a problem that could be as serious as life saving surgery.

Solar Lantern Unit  Kamla Devi Gujjar with her husband at their solar lantern unit-home The Solar Lantern Unit initiative is an employment generation scheme to help the physically disabled. Kamla Devi Gujjar’s husband lost his right hand in a factory accident 7 years ago. She earns a living for her family working at a midday meal scheme facility, while her husband herds sheep, the factory job long gone. What Morarka has done for them is install solar panels on their roof, which charge 20 solar lamps. The lamps, also provided by the Foundation, get charged during the day, and by night are rented out (at Rs 10 per night) by the couple to farmers and students who need light at night. With the erratic power supply in the area, the solar lantern unit has become an important source to supplement the couple’s meager income. There are 11 such solar lantern enterprises in the area, with 20 to 25 solar lanterns in each unit.

Community Kitchens: Sanjha Chulha  Kamla Devi at her Sanjha Chulha-home Another creative initiative of the Foundation is the setting up of community kitchens across the area. Sanjha Chulha is home to Kamla Devi, a widow who works as a National Rural Employment Generation Act (NREGA) labourer when she is not running her kitchen. Also a part of an SHG, she generates anything between Rs 100 to 110 from the kitchen per day. Every day, about 3 to 4 families cook in her kitchen (at charge), all mostly labourers themselves. While Kamla Devi is glad for the extra income, the labourers who come to use the kitchen are also grateful as they do not have the paperwork to get a gas connection and it’s exhausting to cut wood every day. Moreover, in the monsoons, the wood is damp and rendered useless. Therefore, the kitchen comes as a relief. Morarka Foundation assists financially in the setting up of the kitchen but it is run and maintained by Devi. The Foundation also educates Priyanka, Devi’s 17-year-old daughter, who is in university and “wishes to be a teacher someday”.

Misc Other noteworthy initiatives of the Foundation include the Nawalgarh E-library, which allows free and unlimited use of computers and Internet for the youth, aged, unskilled workers, barbers, rickshaw pullers, etc, of the area; the greening of Mukti Dham, a cremation ground in Chailasi village; conservation of the 19th-century ancestral Morarka Haveli; and promotion of Village Walks in the area to encourage rural tourism, thereby generating local employment. |

This article was published in the July 2015 issue of Pure & Eco India magazine.

Good

Good initiative

I am interested in organics farming please add me for all latest Technic of organic farming