By Lily Tekseng. (All photographs featured in this article are the property of the respective outfits mentioned and cannot be used without permission; Featured Photo © Benefit Publishing Pvt Ltd)

Visit ORGANIC SHOP by Pure & Eco India

Everyone wants to buy organic milk nowadays—it’s all over Facebook. Mothers asking which organic milk to ‘subscribe’ to. Fathers readily offering taste and quality reviews, and commenting on which dairy gives the most efficient service. Disappointed customers spewing venom and satisfied ones giving digital pats on the backs of milk providers concerned. Experiences are shared generously as ‘Likers’ eagerly lend their ears in a bid to gather information on which milk is the best, the purest. Meter-long virtual debates break out about the whys, whats, wheres, and hows of milk consumption. O’ Leche, Sarda, Pride of Cows, Astra, 4S, Tru Milk, Kiaro—all protagonists of the digital stories that are spun. All major providers of organic or farm fresh milk.

|

|

|

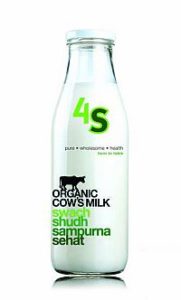

Some of the farm fresh milk brands on the Indian market

In the real world, too, ‘Organic’ is the new buzzword in urban cities. Your correspondent herself, quite impressed by the furore surrounding the term, has switched to Simply The Milk, a Haryana based milk provider that claims to offer “natural fresh pure cow milk”. And from my personal experience, the milk tastes better; it’s sweet and full bodied without being heavy.

“This milk is healthier and free from adulteration. The farm it’s procured from feeds and treats its cows well, which adds to its overall quality. It tastes good and you can have it straight from the fridge,” says Tina Sandhu of Mumbai, listing the attributes that drove her to subscribe to Pride of Cows, which describes itself as being a ‘Farm-to-home’ milk brand that is also “Full of Love”.

“For me, it’s as much about the taste of the milk as it is about deflecting serious health hazards from adulterated milk,” says Meghna Tandon, a PR professional from Gurgaon, who subscribes to 4 S Milk. 4S comes in attractively packaged glass bottles that brand the contents as ‘Organic Cow’s Milk’ that is farm-to-table.

What Exactly is Organic Milk?

Farm-Fresh/Pure/Organic milk providers in India

Farm-Fresh/Pure/Organic milk providers in India

Let us, for a moment, understand the different terms that are being used to describe the same product. Technically, there is no such thing as organic milk in India as there is no certification available for this product currently. There is truth to brands that claim to be organic, however.

When a brand calls itself organic it means its animals are free range and pasture fed; have not been fed any specialised grains or injected with growth hormones, and have been allowed to grow naturally, on a chemical free farmland. Some of them are even fed organic fodder. In most of these farms, the process of milking is fully automated, ie, the cows are milked via pumps, eliminating the instances of human contact and possible contamination. Such milk is also free of chemical preservatives or other additives.

Therefore, organic milk, in the Indian context, is the same as farm fresh milk, as both represent additive free milk from free range cows fed on chemical free pastures. ‘Farm-to-Table’ and ‘Farm-to-Home’ also are synonyms for the same.

While some like 4S and O’ Leche boldly brand themselves as being ‘organic’, others shy away from the tag, perhaps, for fear of unnecessary litigation, giving themselves safer, clearer definitions. “We offer antibiotic free and hormone free, 100 percent pure, cow’s farm fresh milk, ghee and curd. The word ‘organic’ creates room for questions and doubts as it is not legally recognised in the country yet,” clarifies Jaidev Mishra of Sarda Farms, Nashik.

“No one can produce organic milk in the country yet, but this is the closest one can get to it. We offer fresh, preservative, antibiotic and chemical free milk that is untouched by humans in food grade packs,” adds Sachin Joshi of Planet Green Dairy, which caters to Delhi NCR and has its farm in Karnal.

Despite the lack of dedicated organic certification, however, most of these milk providers brandish FSSAI, International Organisation for Standardisation (ISO) and Agmark certifications, which are indicators of standard if not organic content.

Adulteration Driving Growth

The farm fresh milk industry in the country is on the eve of a boom. A second-long Google search throws up tens of organic dairies (big and small) located across the country, selling a litre of milk for anything between Rs 40 to 80 as against the Rs 25 to 50 market retail prices. In conversation with several farm owners, your correspondent found it evident that a strong demand is simmering for all things organic, especially milk. And it is expected to come to boil in the next five years. Why?

In 2012, the Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI) found that over 68 percent of cow milk found in the country did not meet food safety standards. Delhi was found to be the guiltiest of adulteration, with all 70 samples tested being found contaminated. Water was the biggest contaminant, followed by buffalo milk, urea, detergent, glucose, powder milk, etc. Instances have also been reported of sewage water, shampoo and bleaching agents being used to adulterate milk.

The fact that no one knows where the milk they drink comes from, further fuels food safety issues. Milk is first collected from local farmers with one or two cows each by agents, who then pass it on to large corporate companies, who in turn package it and supply it to various parts of the country. To endeavour to trace the life and origin of a glass of milk bought from a retail store, is to search for a needle in a haystack.

Disgusted by the adulteration and literally scared for their lives and those of their children, as well as, backed by growing economic security and comforted by available options, members of the Indian middle class have turned to farm fresh milk in small numbers. With more to follow suit, opines the industry.

New Age Dairies

The coterie of new age dairy farm owners are made up of large companies such as Parag Milk Foods Pvt Ltd (which owns both Pride of Cows and Bhagyalaxmi Dairies) and numerous adventurous entrepreneurs.

After spending over 25 years in USA, Mani Agrawal returned to India but disliked the taste of the milk in Delhi and the fact that no one knew what kind of milk it was. He decided to take matters into his own hands when he lay the founding stone for O’Leche (‘O’ stands for ‘organic’ and Leche means milk in Spanish ), to provide farm fresh pasteurised (heated and cooled after milking) organic cow’s milk to subscribers in the Delhi NCR region.

An O’ Leche delivery van on its way to cater to customers; © O’ Leche

An O’ Leche delivery van on its way to cater to customers; © O’ Leche

Located in Bulandshahar, O’ Leche is spread across 9 acres and houses 150 Holstein Friesian cows, imported from Europe. The fodder fed to the cows is organic, grown hydroponically—a method of growing plants in water, without soil. The cattle is also fed on silage (fermented, high moisture stored fodder) with maize and sorghum (a type of cereal), fresh rye and other grass mixed with grains and minerals—all of it organic.

As with the other organic farm dairies, O’ Leche, too, refrains from hormonal injections and antibiotics. Animal lovers may like to learn the farm is cruelty free, and according to Agrawal, “care prone”. Resident cows are free to roam, sleep on soft beds; their sheds are temperature controlled, they’re bathed daily, especially before milking, and are made to listen to “really cool music”.

The dairy also has its own onsite hospital, with full time medical staff trained in birthing, feed nutrition management, vaccination administration and preventive care.

Gajjender Singh Yadav, owner of 4S Milk, was a fresh faced student at the Shri Ram College of Commerce (SRCC) when he started studying the market for fresh food products and saw the scope for quality food produce in a sector marred by adulteration and an ailing supply chain network. That he had plenty of land available for a prospective venture didn’t hurt, and after zeroing in on milk, 4 S Milk was launched in 2014. It now has 40 Jersey cows of Indian pedigree and up to 270 subscribers in Gurgaon and South Delhi. Not impressive but indicative of potential.

Jersey cows frolic and graze at 4S Milk’s verdant farm

Jersey cows frolic and graze at 4S Milk’s verdant farm

Rakesh Ravindran, director, Astra Dairy, diversified from his manufacturing and export business to the organic milk industry when he realised that quality of milk is a serious concern in the country. “We revisited the old idea of fresh cow milk from the local milkman, except with the finest modern technologies in place. We use no hormones, no antibiotics; and milking parlours ensure lack of human intervention,” shares Ravindran. Astra delivers farm fresh milk to Chennai dwellers and has 1,200 clients currently.

Dairy Tourism

The advent of organic milk and dairies has given way to a new phenomenon—

Dairy Tourism. Many of the organic milk farms are located on picturesque landscapes, away from the city, amid endless meadows and verdant pastures. Located in the lush green Manchar village in Maharashtra, Bhagyalaxmi Dairy is one of the largest private dairies in the country and the largest cheese factory in Asia. It boasts 2,500 cows and is spread over 35 acres. Additionally, it also opens its gates to experiential travellers, to share with them the process behind the production of milk amid the scenic expanses of the farm.

“We have seen rising interest from people to visit the farm, having received 10,000 visitors in the last two years,” says Mahesh Israni, CMO, Parag Milk Foods Pvt Ltd. Many others, including O’Leche, provide dairy tours at a price or even free of charge.

A1 or A2?

There is, however, a slight twist in this plot of happy cows, endless meadows, and contamination free milk utopia. There are two varieties of cows based on their genes: one that produces A1 milk protein, and the other, that produces A2 milk protein. Most dominant cows of today possess A1 genes, while the Indian Gyr cow, which is on the verge of extinction, possesses A2 genes. Recent studies say that milk from cows with A2 genes is far healthier than its A1 counterpart, besides also being compatible with those with lactose intolerance.

Back2Basics, which provides only organic A2 milk, has farms in Gurgaon and Noida. The dairy only keeps gyr cows and grows its own green fodder by using dung manure and biopesticides. “Holsteins, the cows used by many new dairies today, are genetically modified breeds, whereas the A2 gene is found only in few old species of cows, which haven’t been genetically altered. These are also known to have the healthiest milk,” says Sanjay Bhalla, founder, Back2Basics. Ravindran, who plans to add gyr cows to his farm soon, agrees that there is a debate about the A1/A2 issue but so far, it is inconclusive.

Gir cows at the Back2Basics farm, which only sells A2 milk

Gir cows at the Back2Basics farm, which only sells A2 milk

Impediment to Riches

That there is great promise in the farm fresh milk market is undisputed. But that promise has proved a mirage—too far away for some. In 2014, Wholly Cow, Haryana, which used to stock at dozens of elite gourmet stores across Delhi NCR, bid the organic milk market adieu. Along the way, some others, too, have, faltered and been weeded out.

A key reason for organic milk players to fail is the pressures that come from corporate funding. “Companies funded by corporates come under enormous pressure to provide quick returns, which is in stark contrast to the very nature of the venture. The organic milk industry is a slow, time-taking process, which requires long term planning so as not to compromise quality, says Yadav. Thus, dairies find themselves facing the very precarious dilemna of either cutting quality and eventually losing customers, or sticking to quality and losing funders. Either way, the result is not optimistic.

The market certainly bodes better for companies that have ample resources and are not indebted to external financial backing. They can build both repute and clientbase at a steady pace. These are mostly outfits that already have established businesses to support them while the embryo sized organic milk market reaches maturity.

Further to the hurdles faced by dairymen, landholdings are usually small in India, and there is no concept of pasture; cattle management takes extra effort and deep pockets. Despite the notion that the country is brimming with cheap labour, Yadav points out that availability of labour is a major issue.

The lack of knowledge amongst the public about milk and what makes it pure also takes away from what could have been soaring sales. Chirag Aggarwal, head of supply chain, marketing and financial management, O’Leche, says, “The fat content of the milk is often used as a yardstick to judge its quality, which is incorrect. Were people made more aware of the nuances of milk consumption with regard to food safety and health, I am certain, the sales graphs of many a dairy, would be narrating a different story.”

Another major issue in the industry is the fact that certification for organic milk is still not available, leaving meritorious dairymen apprehensive to market their milk as organic—and customers confused by the bevy of names coined to describe pretty much the same thing. Further, a lack of certification means there is no concrete benchmark to measure quality, forcing customers to base buying decisions on word of mouth, clever marketing and random reviews. More worryingly, it leaves space for unscrupulous players to lay claims on purity, even if unworthy of merit.

Chandra Bhushan, deputy director general, Centre for Science and Environment (CSE), comments, “If people are ready to pay more to buy organic milk, they must know what they are getting. Therefore, a standard and certification programme is essential, especially now, when demand is growing.”

Why the government has been tardy with formalising organic certification for milk remains unclear. “The government had previously issued guidelines regarding organic certification of dairy products but the process was interrupted in 2012. Can’t say when they will resume,” says Aggarwal.

Bhalla provides a reason for the delay: “The organic certification is not being given priority as the large companies can never be organic due to their large scale production. Therefore, they’re not pushing for this certification; it’s only smaller, truer-to-quality dairies that are courting the organic tag.”

Meanwhile, White Gold Dairy Farms, Noida, has decided to knock on America’s door. “I want to operate in this unorganised sector in an organised manner. Therefore, I have applied for, and am awaiting American certification for my process,” says Mayank, director of the dairy.

Despite all the hurdles, however, the industry maintains a cheerful front. “Currently, O’Leche is witnessing 200 to 300 growth percent annually. Investors are looking to tap into the potential of the pure cow milk market, and we expect the market to come of age in the next five years,” says Aggarwal.

As the demand for organic milk grows, it is likely to see the birth of more dairy farms, which in turn may fuel the import of cows, beverage technology, and perhaps even cutting edge dairy design. But to quote Yadav, “It will take some time”.

This article appeared in the April 2015 issue of Pure & Eco India

Leave a Reply